This story was originally published in Black Cranes edited by Lee Murray and Geneve Flynn

This story was originally published in Black Cranes edited by Lee Murray and Geneve Flynn

‘The Genetic Alchemist’s Daughter’

by Elaine Cuyegkeng

She dreams of death and rebirth on her mother’s table.

The smell of antiseptic: chemicals, artificial cherries and other-fruit. The specimen on the table. Herself, slipping a needle under the specimen’s skin to obtain samples for reconstruction. Finally, the disposal of the body while the new one grows inside her crimson egg, kicking her little amphibian feet. Later, a telepathic matrix imparts an (edited) library of the Prodigal’s memories. This reinforces the desired traits, knitted carefully into the genome.

In twelve days and twelve nights, there will be a single, perfected being: waking in the specimen’s old room with only a vague, uneasy sense of displaced time. There will be no official record, no trace of the original (save for the genetic profiles, buried deep in her mother’s libraries).

Everyone dreams those strange, mundane dreams of themselves performing their daily rites. The genetic alchemist’s daughter is no different; why should she be? But still, Leto Alicia Chua Mercado wakes as if she were a child waking from a nightmare. Leto thinks: there are fragments of bone and marrow in her pyjamas, in her blankets, her bed. For a moment, her hands are viscous with ruby red.

The Genetic Alchemists

Leto is her mother’s daughter, and so, when she wakes, blinking out crimson dreams in the pre-dawn, the day’s business is the first thing that occupies her. Nothing in Leto’s creation was left to chance; the same is true of Chua Mercado Genetic Alchemy.

Below, the family’s laboratories gestate the fruits of several lucrative contracts. Tiny mermaid embryos, for a techno-prince’s private aquarium. A new variant of winged cat: Bengal Beauties, with jade eyes and leopard spots, jewelled peregrine’s wings. Luminous Moths, ordered by an exclusive fashion house for their silk. There are the Prodigals, the human specimens who will be delivered to their families’ holdings, waking in the original’s old room as if from a dream.

And finally, there are the little Seraphim, tiny embryos swimming in their exo-wombs. The bulk of these are still ordered by foreign CEOs—grateful for the assurance of a rarefied offspring, grateful to be spared the inconveniences of caring for pregnant wives. One day, Leto’s mother hopes, the world will be full of them. There will be no Prodigals, no broken creatures in need of repair.

(Leto feels a tenderness for them. She doesn’t know why—perhaps it’s their shared origins. The fact she knows, and they don’t.

Leto’s mother scoffs at that. You’re not a specimen. You’re my daughter.)

But Leto has always been what she is: the girl with all the gifts, Ofelia Chua Mercado’s irrefutable proof. All the world had seen Leto in her womb, the tiny crimson egg Ofelia created. It made Ofelia’s fortune and her infamy. How the Manilero elite were scandalized! Ofelia had created Leto without the help of a husband, without the blessing of the Holy Apostolic Church (or any church), simply because. Priests cried about the dissolution of the family from their cathedrals, pastors from their multi-million-dollar pulpits. But hereditary heads of state, foreign billionaires, Hollywood queens—all of them came clamouring for Ofelia’s service.

Leto’s mother waits for her at the breakfast table. She is a slender woman, not beautiful but magnificent. She has a cruel mouth, a hard face, a hooked nose as if she truly were the witch the more poetic among the Manila elite call her. Her black hair falls in rivulets down her back. No matter the demands of the day, Ofelia Chua Mercado insists on taking this time: the time to sit down and have a meal with family. She didn’t create a daughter just to neglect her. She prides herself on having better husbandry of children. On the table are buttered toast, salted duck eggs, slices of chilled fruit.

“Today’s clients will need careful handling,” Ofelia murmurs, handing her daughter the day’s dossiers. “I know you’ve managed them before, but darling, today, I need you to resist the urge to gloat.”

Leto opens the dossiers. She understands the moment her eyes fall on the client’s name. She doesn’t smirk; she knows it’s unladylike.

Ever since she was a tiny thing, old enough to be presented in a sad little classroom with portraits of saints, every single one of her classmates had hated her. They called her soulless. They said: You don’t have a papa. And yet, over time, so many of them ended up on Leto’s table. She carefully explained all the reasons why their families elected them for the procedure. She feels that they’re owed an explanation, but she can’t help feeling some satisfaction. She had never disappointed her mother.

“Not one Prodigal,” Ofelia says, sipping her tea, “but three. Can you imagine that, darling? Imagine if they’d come to us from the beginning. It would have spared them so much trouble.”

It’s an old, old story. It is the puzzle that so many familial dynasties have tried to resolve. How does one halt the decline that seems to seep in the third, fourth generation? Sixteen, eighteen, twenty years old, and their beloved offspring showed signs of delinquency, addiction, general malaise, rebellion, depression, of all things. They showed poor scholarship. How does one save a child from themselves? Eighteen years of Mandarin lessons, ballet or music, and Catholic school didn’t fix them. The Church and the promise of heaven can’t fix them.

Manila might have been horrified by Ofelia, the woman who made a daughter. But as the decades passed, one by one, they crept to Ofelia’s door, and begged her for her help. They turned to her genetic alchemy and, over the years, a whisper network has formed between desperate, gossiping mothers, patriarchs over games of golf and exquisite lunches.

Leto feels her fingers itch. Thinks of the discarded original, turning to ash in the furnace while a new, tiny creature emerges whole from Leto’s artistry. All her fellow heirs have hated her: have always hated her. But here she is anyway, granting them a gift unbidden. They will never even know.

Her mother rises and kisses her cheek. “Good hunting, my sweet girl,” Ofelia murmurs, and Leto blushes.

Her mother knows her, inside and out. Better than she knows herself.

The Dowager

When Leto goes to meet clients, she brings her mother’s wares as if they are the trappings of their self-appointed office. In her arms, she brings a winged cat with snow-white plumage, her little feet ending in owl’s talons and one blue eye alongside jade (feline specimens with heterochromia fetch three times the price). A speckled serpent with a forked tongue wraps himself around Leto’s neck like a regent’s gold necklace (base specimen: Atheris hispida). And finally, after a moment’s consideration, Leto carefully selects amber earrings made from the chrysalises of Luminous Moths. She picks up a rose as white as a funeral, a present for the Dowager. She paints her mouth with a neutral pink (edging towards a baby pastel); lines her eyes with modest shadow (Industrial Revolution—a shade popular among her peers). She takes her little slate and programs the nanites in her hair; they colour it a deep black with only the faintest streaks of a foreign autumn.

Leto understands what the heart wants: it wants a useful young woman, modest and helpful, who will solve all their problems with a flick of her manicured fingers. Leto meets clients because her existence says: you could have a helper, a dutiful, reliable heir. The child you need, if only you had asked for our services from the beginning. She revels in clients’ gritted teeth and fingers pressed into their palms—how they hate being proven wrong! She sits herself at the little table, waits for the client to arrive.

And when the Dowager slips into Chua Mercado’s rooms, dressed as if for a funeral (or a cocktail), Leto can’t help it. She rises up and kisses the Dowager’s cheeks like a fond niece. The Dowager closes her eyes; she smells, very faintly, of very fine, expensive whiskey. She shudders; or perhaps, it’s poor Leopold that terrifies her, the gorgeous speckled band winding himself around Leto’s neck, or Anne-Marie, the snow-white cat purring in her arms. Here is Leto, an unnatural thing, decked out in unnatural things. But the Dowager needs her help.

“I have three daughters,” the Dowager says with a rasp. “And they will all be the ruin of me.” Her elegant hand trembles as she sits in the client’s chair. Outside, Leto smiles; inside, a frisson of schadenfreude ticks upwards in spite of herself. She knows the Dowager’s daughters: they are just like every other classmate who’s ended up on her mother’s table.

“Why don’t you tell me what you need, Tita?” Leto asks. Like the witch in the story. What do you need? What do you lack? What price are you willing to pay?

The Dowager is Eva Maria Romano Iglesia—scion of a saintly house, married to a handsome media pastor in her baby-faced youth. She was a woman alone of all the multi-million-dollar pastors: having inherited the position after his untimely death. She preached in Chanel and pearls, wasp-waisted dresses with billowing skirts, and spoke of love and deference to husbands and fathers. She spoke of the sanctity of the family, this woman with no husband, and adoring crowds of women threw money at her. She was the most vicious of Ofelia’s detractors, when Leto and the exo-womb were unveiled. She called Leto soulless. She called Ofelia a fallen woman, creating a child outside the sanctity of marriage, outside the bounds of God’s intended methods.

But now two tiny granddaughters are dead. A son-in-law is set to be buried tomorrow, and the daughters are locked in their rooms in the family compound.

“I need you and your mother to give me the daughters I should have had from the beginning,” the Dowager says. She almost spits. How it humbles her, to be abandoned so by the God who showered her in gold but gave her delinquent children on which to build her church.

“Our congregation needs us,” the Dowager whispers, clutching her Chanel pearls. An entire congregation of lost souls—expensive women with husbands who loathe them, girls who became pregnant too early. They all find solace in the Dowager and her family of perfect women. What happens when the image that gives them so much comfort comes crashing down?

Leto is never really interested in all the clients’ reasons why this has to be done. She’d rather hear from the specimens themselves. Console them on their deathbeds.

“We’ll need to stagger them out,” Leto says. “One by one, to accommodate schedules for other clients.”

“I want it over and done with, as soon as possible.”

“I understand,” Leto says evenly. And nothing more.

(Really, Leto just wants her to anguish over it, just a little longer.)

Silence settles between them. Leto feels the Dowager acquiesce. No one else can help her. She can’t disappear three young women and gain their replacements, their better selves, on her own. She can’t create a replacement daughter, and raise her, not at her age.

The Dowager is old. She is running out of time.

“No one will know?” The Dowager’s hands tighten around her cane.

“No one will know,” Leto says softly. “From head to toe, down to their cells, they will be exactly the same.”

Leto takes the pale white rose, as perfect as a faerie dress. They named it Blanca Nieve. It smells like a perfumed night. She gives it to the Dowager. Places it carefully on the table, along with a lacquered box containing its food. Ten little nightingale corpses.

“People need to see you leave with it in your hands,” she tells her. “So you’ve had a reason to come to us. Feed it with ten nightingales. You won’t be disappointed.”

The next day, a funeral for the Dowager’s son-in-law is held in her stained-glass church. The cathedral arches are snow-white with roses, and they spill down the steps of the church, singing with bell-like voices.

No one even sees the bones.

Faith

She starts with the youngest. Why not?

They take her from the family compound. They place her, fast asleep, on Leto’s table in the lab. Faith is a delicate snow-white beauty: long limbs, a small head, the fair skin that Manileros prize so much. It’s at odds with Faith’s reputation.

Leto waits, and watches as the specimen slowly blinks herself awake. The upsurge in fear when she realizes that she’s strapped to the table. When she realizes that she’s not alone.

Leto doesn’t see what she does as revenge, as former classmates have accused her when they have woken up to find themselves in her lab. She sits with the specimens, waits for them to wake up. It feels wrong to her, simply destroying the originals without explaining why their families requested the procedure. She hopes that a vague memory of that conversation settles into the client’s cells. When they perform the process, create the new, perfected specimen, the Prodigal will not relapse.

“Faith?” Leto says. Her words come out muffled behind her mask. The girl stops struggling; she recognizes Leto’s voice.

“Oh God,” says Faith, and the pretty girl laughs. “All the stories they said about you are true.”

Leto’s hairs prick up at the back of her neck.

When they were children, Leto was the witch’s daughter. Now, as adults, she is her mother’s right hand, her coolly competent heir and that is where her story ends. All the specimens returned to the client families have had their memories edited: they know nothing of her mother’s labs. But her classmates know nothing of Prodigals, of Leto’s part in the process. They know nothing of the Procedure. It’s in their parents’ interest: that their children know nothing. They’d rather forget the unpleasantness and have their baby back (they never really will).

“Do you know why you’re here?” she asks Faith. Faith laughs and pulls at the straps.

“I killed my sister’s husband,” Faith rasps. “We did it together, you know. Me. Charity. Harmony. We pushed him off the balcony.”

They’d said it was an accident. Pat del Rosario—beloved husband, beloved son-in-law—falling over the balcony in the family’s multi-million-dollar compound. Thank God, the Dowager had board positions on various media boards: his death was announced without mention of murder or suicide. They had locked Faith in her room until the funeral and she had appeared with the rest of the family, her stony face easily interpreted as a perfect mask of dignified grief.

“I did it knowing you’d show up,” Faith whispers.

“You knew nothing of the sort,” Leto says. Her voice is even, but under the table, her hand shakes.

Faith has no reason to believe Leto would show up. She has no reason to believe in her mother’s lab. Leto is not a fairy tale, the way the Prodigals she perfects are fairy tales. They emerge perfect and whole under her fingers, blessed with cool-eyed competence, the smothering of their genetic demons.

“Do you even want to know why?” Faith asks.

“I know you want to tell me,” Leto says.

It doesn’t matter what they tell her; the procedure will go ahead anyway. But it’s as if she’s a confessor tending to a penitent on their deathbed. How can she say no?

You’re not a specimen, Ofelia had told Leto. You’re my daughter.

But still, the fact remains: Leto was created to prove the viability of her mother’s product, the efficacy of her mother’s services. Ofelia edited Leto’s genes. She edited them for beauty, for genius, for musicality, an affinity for maths and languages, all those things that the ultra-rich crave in their children. They like to feel as if their genes have given rise to better stock, better product.

Leto was engineered for obedience, which meant she was inclined to recognize her mother’s authority in all things. Her mother had been frank about this: there was no point in raising a child who spurned all her gifts. From the moment Leto stepped inside a classroom, she had excelled, surpassing her peers. It gave the elite of Manila something to consider, even as they called her soulless. When their beloved babies grew up, showing signs of rot by the time they reached their teens, they turned to Ofelia Chua Mercado and her helpful, perfect daughter. Who swap out imperfect specimens for better ones. Or at least, they edit the genetic code, so they are more inclined to conform to their parents’ expectations. They’re like fairy godmothers, granting obedience as a gift.

Faith had failed from the beginning. Even when she and her sisters were little, when the Dowager paraded them around as her little saints, Faith was infamous for her rage. There was a party, when a group of boys held her down to take her photo (wasn’t it sweet? Babies and their games!). She’d pushed one of them down the stairs, and he broke his leg, right there on the Dowager’s immaculate floors. When they were all older, there was another incident, another more grown college party, when she’d taken out someone’s eye.

The Dowager said: they’d hoped she’d grow out of it. That time and patience and their guidance would temper her. It honestly surprised Leto that it’s taken Faith this long to come to her table.

(Leto’s mother said, scoffing, that they should have edited Faith’s anger out of her, long ago. Leto had wisely kept quiet. She doesn’t blame Faith, the way her mother did. But she knows what traits are desirable and what aren’t—they don’t like rage in little girls.)

And now there’s a dead body that they’ve had to cover up with bribes and ritual, and a snow-white funeral.

“He killed Charity’s babies,” Faith snarls. “Did Mommy tell you that? He killed her girls.”

It was in the dossier—a sad obituary in the Manila Times of the Dowager’s twin granddaughters. But babies often die for strange, unknown, and unknowable reasons. Especially when they’re so small.

“He put stuffed toys in their crib,” Faith says. “It’s a SIDS risk: everyone knows that. They kept telling him to stop; he laughed and kept doing it. Look, she loves her little teddy. What’s the harm? Everyone said: Men don’t raise children, it’s not in them. You can’t expect them to understand. It was Charity’s responsibility: after all, she was their mother.

“Charity couldn’t stay awake forever. She tried. We all did. He found reasons to keep us away. And one day she found him standing over their crib with a pillow—and her baby girls were dead.” She closes her eyes. “A house full of people who were supposed to love them, and they all said she was hysterical. They didn’t believe her. Poor Charity. He barely cried.”

“Why would he do that?” Leto asks.

She really shouldn’t have asked. All Faith wants is to unburden herself.

“He wanted boys,” Faith says. “It’s not as if he hid that. He was so disappointed when they came out! And Charity was so happy—his disappointment was such a small thing to her, at least in the beginning. That she loved something he didn’t.”

“Annulment was an option, you know.” It’s not that she objects to what Faith did; it’s that she should have been clever about it. She starts thinking of ways to snip the rage out of her, or at least temper it. They can modify memories to reinforce caution.

“Annulment isn’t part of our brand,” Faith says. “It’s not an option for us. Can you imagine the scandal? Lola would kill us first. Mommy would.”

That, Leto thinks, unfortunately is true.

“I’d have been more careful about it than you,” Leto says. Faith laughs.

“We were past careful,” Faith says. “After he killed the girls. After they all said Charity was hysterical and not thinking clearly. They even blamed her: Lola, Mommy, our aunts. We shut them up when we threw him down the balcony.”

Leto starts prepping her needle. She needs to draw blood; their work is easy, really. They have such a rich source of DNA.

“So what are you going to do?” Faith asks. “Replace me with a soulless little drone? A more palatable version of me?”

“Don’t be so dramatic,” Leto says. “I can’t make or remove a soul. I’d make a version of you that wouldn’t have gotten caught.”

It’s not quite what Faith’s mother would have wanted. It’s not what Ofelia Chua Mercado would have wanted. But there is no one here to gainsay her decision.

She’s not sure why or how she decided this: that Faith is entitled to her anger. But here she is.

“It’s alright,” Leto says, and she is back on familiar ground. “It’s alright. You won’t even remember this happened. The you that wakes up won’t even remember this.” And if the new Faith doesn’t remember and the old Faith is simply erased, does Faith even suffer?

She lets Faith see the tiny little selves, swimming in their little crimson eggs, before she puts her to sleep. It seems to calm Faith: watching tender little creatures made from her bone and marrow. Leto dresses the new specimen herself when she emerges, perfect and whole. The new Faith will be little more calculating, a little less given to rages. If the new Faith does need to act on her rage, she will take better care not to get caught. The Prodigal is returned to the family. The Dowager sends back a message, saying: Faith is much improved. Leto imagines the Dowager breathing a little easier even as Faith is counting her grudges and biding her time. Counting down the days, until it’s all done.

Leto schedules the next two procedures. She takes her time.

Charity

She was the last person Leto had thought would end up on her table.

The middle sister: kind-hearted and soft, the kind of girl who deflected other people’s faults. The fairy tale girl people say they want but, in reality, isn’t equipped to keep a dynasty together. Still, she had that fairy tale wedding, married the boy her family picked for her. The Dowager was very clear about her specifications: they want their sweet girl back, before she went wrong.

“Really,” Leto told her mother wearily, over chai tea and congee for breakfast, “they want a Charity who doesn’t remember how much her family failed her. They want a Charity who won’t make them feel guilty, every time they look at her.”

“If that’s what they want to believe,” Ofelia said. She shrugged her elegant shoulders. It’s cheating, but it’s not quite cheating, is it, if a Prodigal is exactly the same, just slightly improved? It’s the improvements they focus on.

Leto didn’t tell her mother about what Faith had said. It’s not that she believes Faith, exactly, but…

When Charity wakes up, when she sees Leto, she looks almost resigned. There’s no shock. Ice pricks at the back of Leto’s neck. Charity should be shocked. Charity should cry for help. Why doesn’t she?

“I knew something was wrong,” she says. “When Faith came back… She wasn’t herself.”

Leto doesn’t answer.

“Poor Faith. Did she feel anything? Was it fast?”

“What can you possibly know about the procedure?”

Charity laughs, a sad little laugh that almost sounds like affection.

“We all talk about it, you know,” she says. “All our old classmates, all our old friends.”

None of you were ever my friends. Leto digs her nails into her palms. She is not…she is not supposed to be the monster in anyone else’s story. She’s more than that unveiled creature in the womb, more than the girl in the schoolroom, more than the witch’s baby everyone decided they should hate.

“I’m frankly surprised that you don’t know. I would have thought that your mother would have told you. We could never match you in scholarship, but we’re not stupid. Sometimes an old classmate would show up and…they weren’t quite themselves. They would remember things—but in slightly different ways. We heard about the oldies’ little whisper network. They say there’s a little dungeon somewhere—where all the bodies are kept. There’s a little lab where you clone tiny little creatures to replace us. That you sell our souls yourself.”

Leto’s heart is beating fast.

There is no reason. There is no reason why Charity and her friends should know. The specimens’ memories of her mother’s workshops are wiped. The Prodigals are returned to their rooms, and they don’t remember—they don’t remember anything of their time as tiny little creatures in blood-red eggs, their hatching.

If what Charity says is true and there are whispers of the process, and Leto’s part in it… How could she not know that she has turned into a story she has no control over? How could her mother not know? She feels like she’s back in that dreary little room again: her classmates whispering poison, spinning stories she has no control over.

Charity watches her face. “Do you remember?” she asks. “Do you remember anything—from before?”

“Before what?”

Charity closes her eyes and sighs, as if she is very tired and ready to go to sleep. She opens them again, and her eyes fix on Leto. “I wouldn’t tell your mother about this conversation if I were you.”

“We tell each other everything,” Leto says.

“Do you?” Charity asks. “Do you really? Do you ever wonder about the little gaps in your memory—”

She doesn’t have to pay attention to this. She doesn’t.

“Look at me,” Charity says, her voice soft and urgent. “I did everything my mother wanted. I married a boy she wanted. I gave up the idea of a master’s degree in science. And still—look at where I am right now.” Leto twitches, remembers her dreams of little feet, a crimson world.

“I wasn’t expecting to have to destroy everything I was when I married,” Charity whispers. “I wasn’t expecting to destroy everything I loved. That wasn’t the bargain I thought I made. Do you remember your Bella Norte?”

When she was fourteen, Leto had engineered little bees who sang like bells and were nocturnal. As sweet and docile as Charity. She’d been frankly surprised that the Dowager had purchased a specimen from Chua Mercado Alchemy. A birthday gift for her middle daughter, who later became obsessed with beekeeping.

“They never really caught on,” Leto says. That was the trouble with new patents.

“Do you remember?” Charity asks. “Do you remember making them for me?”

Leto just stares. She’d done nothing of the kind. She made them, Charity ordered them, and that was the end of it. Charity sighs, softly.

“I kept beds and beds of nocturnal flowers to feed them. I did everything you told me to, even when you stopped answering my letters.

Nocturnal roses, honeysuckle, lavender. Leto can’t even remember why she made them: only that she did.

“Mommy and Lola never approved. Pat wanted me to stop: they were dangerous to me and the baby. Who knew what they were picking up while they were dancing in the dark? Who knew how reliable the patent was, how docile they really were? I went on a trip to the States; I came back to find most of my hives burned. Lola said: But it’s such a little thing. Mommy said: You have babies now. You won’t even notice they’re gone.”

Charity closes her eyes. “And then the girls turned out to be girls. We didn’t even want to know—he was so sure God would give us what he deserved. I took their blood. I cut their hair. I wanted something to remember them by, just like I kept the bees to remember you.” She breathes in, breathes out. Looks over at Leto, whose face is carefully blank.

She would have no reason. Her mother would have no reason to remake her. Leto is perfect, has been perfect, since the beginning. She was engineered for beauty, for intelligence, reliability. There is nothing that Leto wants, outside of what her mother needs.

“They were right,” Charity whispers. “Oh God, they were right.”

Leto doesn’t answer. She preps her needle.

“Listen to me,” Charity says, before she slips off to sleep under Leto’s needle. “You’re not so different from us. Someone should have told you that from the beginning. I’m sorry we didn’t.”

Charity is easier, in many ways. They keep the base genetic profile. They edit her memories. Faith did it. Harmony did it. Charity just watched. Leto goes through an entire album of memories, editing things out, snipping inconvenient ones.

When the new Prodigal wakes in her room, she is more certain of her mother’s authority, of her mother’s love and adoration. The need to defer to her authority. She won’t remember that conversation with Leto, in the lab below.

Leto should talk to her mother. She should talk to her, but something stops her, every time. Leto stays in the lab, watching over the dreaming specimens. Cinderella, over the turtledoves that shake gold and silver over her. She thinks of the ashes of every discarded specimen, feeding her mother’s roses. Faith, Charity, an endless, endless parade of names before them.

And she wonders, she wonders. How many of them were her? How many dreams has she had, of a crimson world and kicking feet? Can she count all the times she might have been remade? She wouldn’t even know when it began, what had been the starting point. She walks into the garden at twilight, where the apiaries of little Bella Norte are kept. Their little feet brush against her cheek like a kiss.

Do you know more of me than I do? she asks them.

Do you?

Harmony

The eldest daughter escapes.

She must have seen the writing on the wall, Leto muses to herself when it happens. The Dowager is beside herself. It would not have happened, it would not have happened, if Leto had done all three of them at once like she had asked.

You should have known better than to let the other girls out, is all Leto thinks. Ofelia lets the Dowager know, calmly, that matters are being handled and shoots Leto a look. Leto understands: she wants Leto to fix it. The foundations of the world her mother is building depends on Chua Mercado’s reliability, their reputation. She needs to undo the damage she’s caused.

But Leto spends some time in the garden, among the specimens and patents that never quite caught on. She spends some time with the Bella Norte bees, waking in the moonlight, settling on Leto’s dress like golden dust.

You made them for me, said Charity. Why would Leto do that? What did she owe her?

She considers that Charity and Faith may be right, that her mother has been wiping her memory, altering her like a story that she can’t quite perfect. She should be terrified. She should be outraged, but all she feels is hollow. She wonders if anger was edited out of her too.

“I don’t know what to do,” she says, honestly, to the Bella Norte bees, as if they could answer her.

They track Harmony down in a shabby little street in Binondo, in a shabby little room. Leto insists on going herself. After all, it was her mistake.

At that, something inside Ofelia seems to untwist and loosen. She kisses Leto on the cheek. She says: She knows Leto will make it right. Everyone makes mistakes. We all learn from them. We make ourselves perfect.

Leto lets herself into the shabby little room, and there is Harmony, waiting.

The survivors of Charity’s bees surround her, drinking sugar water. Harmony is tall and striking, even with her hair slick with the humidity and the lack of care over the past few days. Charity was the sweetheart, Faith was the baby, but Harmony was meant to be their mother, all over again. It must have galled the Dowager, when Harmony picked her sisters over her mother. That was not the natural way of things.

Leto isn’t sure what edits to make to improve those outcomes.

“We all know you’d come for us, you know,” says Harmony. She doesn’t move. The bees settle around her, as if she is their saint.

“So I’ve heard,” says Leto. Harmony raises her eyebrow.

“What do you remember?” Harmony asks, point blank.

Leto says nothing.

“What do you remember?” Harmony asks. “How many times did she make you over, so she could start all over again, a clean slate?”

Leto thinks of the ashes in her mother’s garden. Whether any of them are made up of her former selves. She wouldn’t know when her mother started. She wouldn’t even know where to begin.

“I know about Charity’s daughters,” she says, her voice hollow. “I know about the bees.”

Harmony sighs, and her shoulders slump over.

“We didn’t know,” she says, “if she’d remake you, over and over again. Just to make sure you couldn’t remember. Do you remember? Making the bees for Charity? Do you?”

Leto feels breathless. A little bella norte lands on her cheek.

“She cried when you stopped answering her letters,” says Harmony. “When we passed by each other and you acted as if you didn’t know her. And later—when classmates came back, from rehab, from sabbaticals, from tours, not quite right, well, we all wondered.”

It’s like a knife to her ribs. She doesn’t—she can’t feel anything.

Harmony gives her a box.

“I’d do it again you know,” she says, between her teeth. “I would pick Faith and Charity, every time. Every time. Hollow me out, empty me of all the inconvenient things my mother wants gone, and I’d still make the same choice.”

“What’s inside?” Leto asks.

But she already knows.

The Dowager sends payment: all three Prodigals, successfully remade. She even gifts Leto with the survivors of Charity’s bees. They have no use for them, and the girl is getting married again in the fall. Another fairy tale wedding. Then: one for Faith, and one for Harmony. She’s already signed contracts for little Seraphim to be made.

“Well done,” Ofelia says, and kisses her cheek. Another death, smoothed over. Because these girls wanted something outside what they should want.

What does Leto want? Nothing except her work. There’s nothing that her mother left her.

So she creates a second variant of the Bella Norte, from the daughters of Charity’s bees. They have Faith’s anger; Charity’s love; Harmony’s loyalty. And inside, inside, they contain slivers of memory, two baby girls avenged by their mother and aunts.

Leto’s daughters have no debut: they are not presented to the world the way Leto was. Instead, she lets them fly wild.

That year, the Dowager and her congregation will be haunted at night time by bees that sing like wind chimes, that smell of baby’s breath, and build cathedrals inside her church. At her wedding, Charity will turn to look at them, and she won’t know why she feels joy and heartbreak. Faith will wonder as she lets them settle on her shoulders and Harmony will feel a strange peace, even as the bees murder her mother’s congregation.

They’ll say it’s a miracle, that the three of them are left alive.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Elaine Cuyegkeng is a Chinese-Filipino writer. She grew up in Manila, where there are many, many creaky old houses with ghosts inside them. She writes about eldritch creatures, monsters with human faces and the old, old story of art and revolution. She now lives in Melbourne with her partner.

Elaine Cuyegkeng is a Chinese-Filipino writer. She grew up in Manila, where there are many, many creaky old houses with ghosts inside them. She writes about eldritch creatures, monsters with human faces and the old, old story of art and revolution. She now lives in Melbourne with her partner.

Elaine has been published in Strange Horizons, Lackington’s, The Dark, Rocket Kapre, and now, Pseudopod! You can find her on @layangabi on Twitter.

FIND MORE BY ELAINE CUYEGKENG

Edited by Emerian Rich

Edited by Emerian Rich

Relationship with Cemeteries, Death’s Garden Revisited, and Morbid Curiosity Cures the Blues: True Tales of the Unsavory, Unwise, Unorthodox, and Unusual. Her short stories have appeared in the books Best New Horror #27, Strange California, Sins of the Sirens: Fourteen Tales of Dark Desire, Fright Mare: Women Write Horror, and most recently in the magazines Weirdbook, Occult Detective Quarterly, and Space & Time.

Relationship with Cemeteries, Death’s Garden Revisited, and Morbid Curiosity Cures the Blues: True Tales of the Unsavory, Unwise, Unorthodox, and Unusual. Her short stories have appeared in the books Best New Horror #27, Strange California, Sins of the Sirens: Fourteen Tales of Dark Desire, Fright Mare: Women Write Horror, and most recently in the magazines Weirdbook, Occult Detective Quarterly, and Space & Time.

They? and Gathered Flowers, Stones, and Bones.

They? and Gathered Flowers, Stones, and Bones.

other than to say he is always, always turning normal on its head and seeing where his imagination takes him. He rarely knows where a short story is going till it’s finished.

other than to say he is always, always turning normal on its head and seeing where his imagination takes him. He rarely knows where a short story is going till it’s finished.

author.

author.

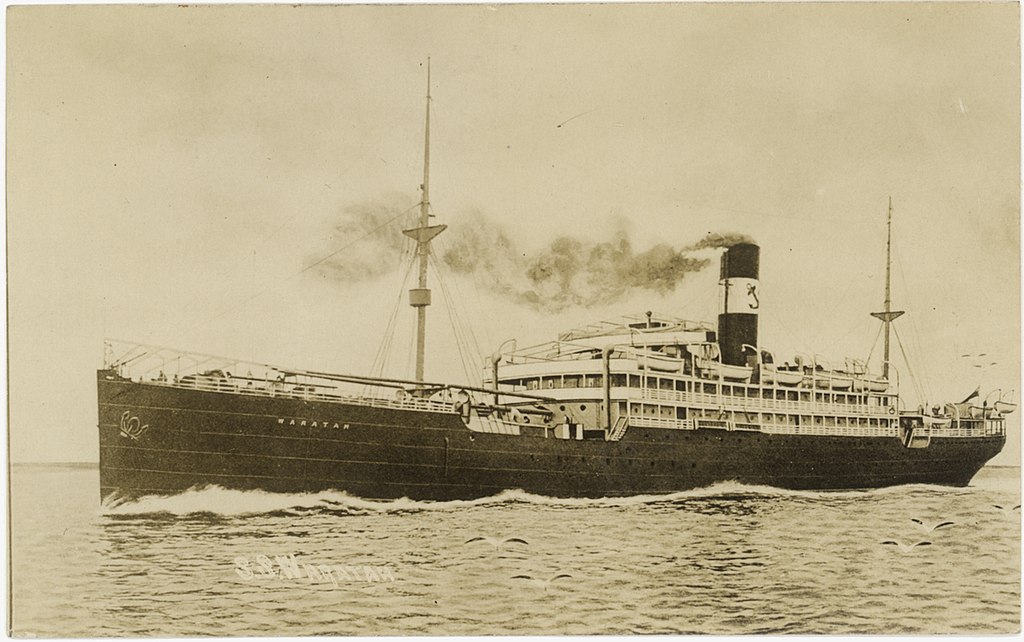

My story in Haunts and Hellions, “Hungry Masses” was based upon a real ship that was lost at sea. The SS Waratah (named after an Australian flower) was a passenger and cargo ship built in 1908 by the Blue Anchor Line. Its route was from England to Australia, and then back to Europe via Cape Town, South Africa. In July of 1909, it vanished with 211 passengers and crew aboard. It has never been found.

My story in Haunts and Hellions, “Hungry Masses” was based upon a real ship that was lost at sea. The SS Waratah (named after an Australian flower) was a passenger and cargo ship built in 1908 by the Blue Anchor Line. Its route was from England to Australia, and then back to Europe via Cape Town, South Africa. In July of 1909, it vanished with 211 passengers and crew aboard. It has never been found.

Daphne Strasert

Daphne Strasert B.F. Vega

B.F. Vega them.

them. an affinity for writing flawed female protagonists who occasionally murder. Her writing credits include Cemetery Gates, Kandisha Press, and Curious Blue Press among others.

an affinity for writing flawed female protagonists who occasionally murder. Her writing credits include Cemetery Gates, Kandisha Press, and Curious Blue Press among others. stay with you long after. You can find her connecting with readers on social media, educating America’s youth, raising two brilliant teenagers, writing horror-infused music reviews for HorrorAddicts.net, trying desperately to get that back piece finished in the tattoo chair, or headbanging at a rock show near her home in the San Francisco Bay Area! Stay Tuned for more Rock ‘n’ Romance.

stay with you long after. You can find her connecting with readers on social media, educating America’s youth, raising two brilliant teenagers, writing horror-infused music reviews for HorrorAddicts.net, trying desperately to get that back piece finished in the tattoo chair, or headbanging at a rock show near her home in the San Francisco Bay Area! Stay Tuned for more Rock ‘n’ Romance.

podcast horror hostess with an international audience and a vehicle with which to promote, HorrorAddicts.net.

podcast horror hostess with an international audience and a vehicle with which to promote, HorrorAddicts.net. Author N.C. Northcott (they/them) was born in London and now resides on a plateau near a river with two cats and Yorkshire Terrier. They love writing urban and historical fantasy but also dabble in horror, steampunk, science fiction, mystery/thriller and romantic comedy. An avid photographer who also dabbles in painting and procrastination, their next project is an urban fantasy about a transgender sorceress set in modern-day America, near Boston. As they just invested in a magical electric bread maker, there will be somewhat less writing and considerably more sandwiches in their future.

Author N.C. Northcott (they/them) was born in London and now resides on a plateau near a river with two cats and Yorkshire Terrier. They love writing urban and historical fantasy but also dabble in horror, steampunk, science fiction, mystery/thriller and romantic comedy. An avid photographer who also dabbles in painting and procrastination, their next project is an urban fantasy about a transgender sorceress set in modern-day America, near Boston. As they just invested in a magical electric bread maker, there will be somewhat less writing and considerably more sandwiches in their future.

Bio: John Linwood Grant lives in Yorkshire with a pack of lurchers and a beard. He may also have a family. When he’s not chronicling the adventures of Mr Bubbles, the slightly psychotic pony, he writes a range of supernatural, horror and speculative tales, some of which are actually published. You can find him every week on greydogtales.com, often with his dogs.

Bio: John Linwood Grant lives in Yorkshire with a pack of lurchers and a beard. He may also have a family. When he’s not chronicling the adventures of Mr Bubbles, the slightly psychotic pony, he writes a range of supernatural, horror and speculative tales, some of which are actually published. You can find him every week on greydogtales.com, often with his dogs.